|

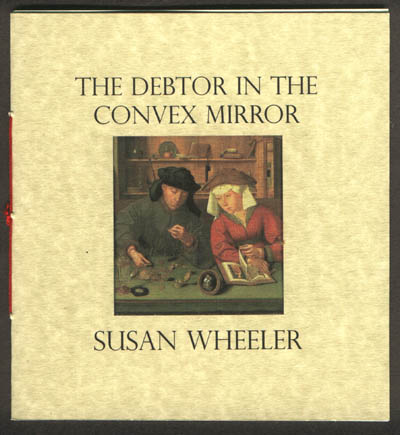

142x155 mm, 24 pages, 250 gsm Gold Strata card cover with colour illustration, green endpapers, hand sewn with red twist. ISBN 1 903090 43 1 Susan Wheeler's books of poetry include See below for an extract from The Debtor in the Convex Mirror. Click here to read the full text at Boston Review. Click here to go to Susan Wheeler's home page. |

|

From Boston Review. Winner of the Sixth Annual Boston Review Poetry Contest Introduced by Richard Howard

|

|

from The Debtor in the Convex Mirror.

He counts it out. By now from abroad there are shillings and real – Bohemian silver fills the new coins – but his haul is gold, écu au soleil, excelente, mostly: wafers thin and impressed with their marks, milled new world’s gold the Spanish pluck or West African ore Portugal’s slaves sling. The gold wafers gleam in their spill by the scale. Calm before gale: what bought a sack a century before almost buys a sack now; the Price Revolution’s to come. A third of a mason’s – a master one’s – day’s wage funds the night’s wine, Rhine, for his crew after a big job wraps up. As for dried herring, his day’s wage would buy fifteen mille for a big do; his workers, just nine – 18 stroo. Calm in his commerce is the businessman, and his wife, their disheveled shelves: she turns a page; her hands are in God but her gaze is on ange-nobles and pearls, weights and gold rings – one florin in pan, one in his hand. What sync they are in: calm their regard, luxe, volupté their mien. Fur trimmings on jackets, gemstones on fingers – while the debtor in the mirror has spent what he has on the red hat he’s in. Prayer book illumined: luxury that, and to ignore: only more. Calmed by the calculation of interest, though the figure’s been clear for a good quarter hour, the moneylender withholds it and waits: the debtor is better with fuzz in his head. In truth, he’s distressed: cares like the shield impressed in the écu dint the meet of his brow beneath the red hat. What’s he reading? Or faking? Caught in the curve of an office’s alarm, an anti- to crime, a drugstore’s big boon long centuries to come, the debtor – about to receive knell to what peace he might otherwise recall – worries his page. Ability for reading silently may not be his; the lender’s wife puts him to shame, though the shame in this is the least of his shames. In the yard beyond her waits one of his lienors for the gold of another. Schoolmarms ahoy. Scrap history, the parable, the prayer of the illustrated hours she trembles to hold. He’s got his gold, she’s mes- merized or not by its sheen, the debtor’s lost to our reflecting of him – but it’s without, a measurement is made – a figure’s gesture on the gravitate street, the fury of a face in its face, behind the door ajar, the fingers of the lienor demarcating fast the size of a peck or a pecker not so. The debt is as large as a giant’s back turning, large as a vulcanic forge. And fragment of the debt imbursed – size of its toy – intense regard. Fume individually, fume borrower, clipper, catcher, coiner, getter, grabber, hoarder, loser, lover, raiser,

spender, teller, thirster – scrivener lays out upon collateral, but what has the red-hat? Zero and then sum.